The war on drugs is a ‘war against women and children’

More than 20 years since Amy Case King served her last prison sentence for drug-related charges in the US, the conviction still affects her.

‘Criminalization is more harmful in the long-term because it doesn’t address the underlying drug use,’ she says. ‘The impact lingers long after the completed sentence. Having to report a felony on job and rental applications, and higher education financial assistance is like double jeopardy. It’s a continued punishment that impacts your access to basic needs such as shelter, food and clothing.’

A new report from the Global Commission on Drug Policy (GCDP) reveals over three million people were arrested for drug-related offences in 2023, with almost half of executions worldwide related to drug crimes. The number of women in prison globally for drug-related offences has increased by 17 per cent since 2010.

But while governments are spending $100 billion a year on the ‘drug war’, prohibition has failed to control the illegal drug trade, resulting in rising overdose deaths, strained criminal justice systems and ‘grave violations’ of human rights.

‘These policies are simply not working – and we are failing some of the most vulnerable groups in our societies,’ said Volker Türk, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

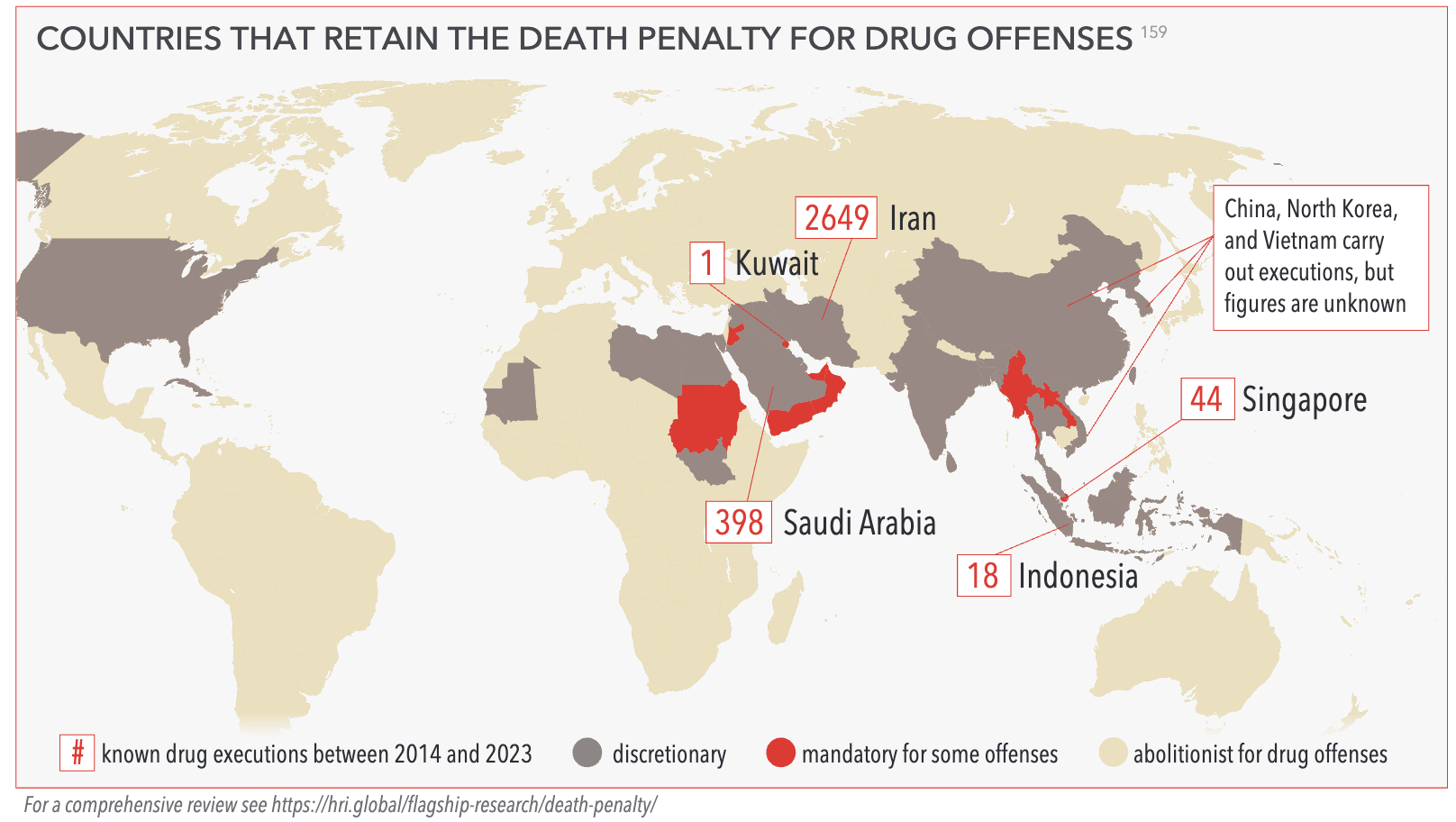

The GCDP report, co-authored by 16 former heads of state and UN representatives, calls for a shift towards strategies rooted in health, human rights and social equity. The report calls for an abolishment of the death penalty for drug offences, criminal justice reform, the closure of compulsory drug detention centres and a reallocation of funding from harmful drug control policies to harm reduction and other social services.

Rates of drug incarcerations among women are rising in every continent outside of Europe — globally 35 per cent of women in prison are incarcerated for drug offences, compared to 19 per cent of men. Nearly 50 per cent of women incarcerated in Colombia are detained for drug offences (93 per cent of whom are mothers). In Thailand, where the prison population has doubled since 2016 thanks to ‘anti-drug’ campaigns, 92 per cent of women on death row are there on drug charges.

Louise Arbour, former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and a co-author of the report, says the rise in women incarcerated for drug offences could be due to an increase in ‘low-level law enforcement’ which ‘disproportionately impacts marginalized groups’.

Putting women in prison for drug-related offences should always be a ‘last resort’, says Arbour. As the primary caregivers to children and elderly relatives, the burden then falls to other women in the community, or the state care system.

King says the incarceration of either parent reduces the income available to support the child, ‘breaking up the family unit, keeping it in poverty cycles and putting additional stress on already difficult life conditions.’

‘Whichever way you look at it,’ she adds, ‘the war on drugs is a war against women and children.’

— Sarah Sinclair (@sarahlsinclair_)

📰 Read the GCDP's full report which includes recommendations for drug policy reform

👉 Follow: Women in Prison, an organization supporting women affected by the criminal justice system in the UK

✅ Take action by emailing your MP to discuss the impact of drug laws in your community. Use Anyone's Child email template here.

🎧 Listen to the Taxcast podcast about how the US war on drugs is linked to tax evasion. Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

👀 ICMYI: Amy Hall's piece from our Sept/Oct issue: What if ... cannabis legalization was actually just?

Like what you've read? Support us with a tip.

Are you a freelancer? Pitch us a story.

Looking for more? Listen to our podcast The World Unspun

Subscribe to New Internationalist magazine and get Currents absolutely free!